With almost no reference as to the other field party members, Beadell recalls this reconnaissance in Chapter 12 (pp.143-154) of his 1965 book Too Long In The Bush as follows (with minor edits) :

|

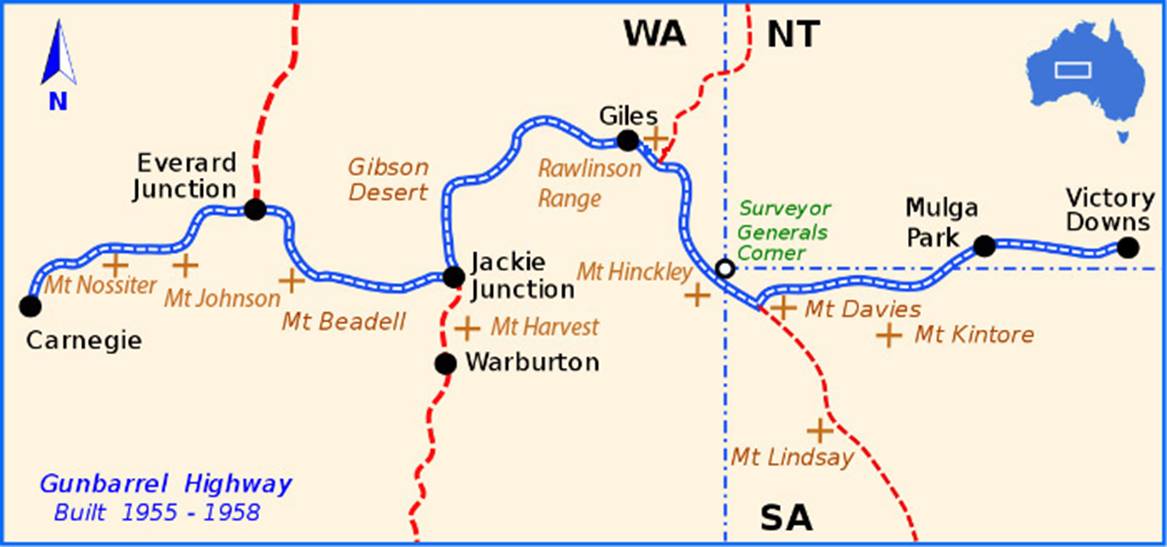

It was to the north of the mission and to the west of the new road that a prominent knoll had been seen as a likely start for the latest preliminary survey as far as our destination. Forty miles back it had looked something less than twenty miles away, meaning that it would be a satisfactory distance from the previous survey station chosen, and although it was probably only a higher spot on a sand ridge it would give the elevation needed to see farther. From a rough plot of the cattle station homestead [Carnegie] which was to be our objective, and our present known position on the road, the overall distance to be covered appeared to be about three hundred miles.

…everything else had been made ready and the little cavalcade of vehicles in the expedition were soon on their way. Plans were made for two of us to forge ahead to the next visible hill or rise, leaving the other three at the previous rise, and for sun flashes to be sent from a heliograph to indicate that each could be seen from the other. Then, when a reply was sent back from the advance pair and compass bearings were read, both groups could move along, the front ones cutting a fresh set of tracks, and the others following in the day-old ones. That each point was clearly to be seen from the ones on either side was, of course, vital to the feasibility of the survey.

In addition to the four Land Rovers, we had another vehicle of rugged construction with the body work designed and built especially for carrying bulk petrol, food and water [A Damlier-Benz Unimog – please refer photograph below]. It was certainly able to travel over the roughest ground, but the tray with its unusually high and heavy load raised its centre of gravity far beyond what the makers had in mind, and this was to be the cause of much consternation to the driver during the weeks ahead. I had been extremely doubtful when I first saw the type of bar tread tyres it had that they would be any use in this sort of country, but at this stage nothing could be done about them and they had to be used.

We arranged for the officer from our headquarters and the aboriginal affairs man to stay behind with the supply vehicle, while the surveyor from the department that would be establishing and using the stations and I would go in front. Where the proposed point ahead was a definite or obvious hill, both groups could move on together, but we usually found that many days would elapse before the two parties met.

The first knoll was reached in fifteen miles without much trouble, for we were travelling with the sand ridges which ran east to west. But the supply vehicle was already swaying violently over the spinifex clumps off the made road. At this stage the driver thought lightly of it - a slight nuisance only and even a little fun.

Our hill turned out to be just a higher spot on an already formed sand ridge, but it afforded a clear view all around, and we were pleased to see the blue shape of a more substantial outcrop to the west. The rocky outcrops we had skirted earlier in making the road were quite clearly visible and it seemed that we were off to a good start.

Prismatic compass bearings were read to every prominent feature and carefully recorded, as well as descriptive notes identifying the land mark. It was planned to carry out the same work at each point, and from time to time positively fix points by latitude and longitude observations to the stars, so that when we noted the vehicle speedometer mileages we could plot our course exactly; this would be invaluable in the subsequent construction of the road.

The surveyor with whom I travelled was a man I'd known for many years. We were both in the Army Survey Corps during the war, and I had the highest respect for his ability in every field of this work. I had not as yet been camping with him like this, but I knew by repute that he had proved himself capable of being able to live on a rock-bottom minimum of food and water for greatly extended periods, and continue working every night up to hours that would be a physical impossibility to most people after long and vigorous days in the bush. After the last rays of light had gone on the first day out, we stopped to camp, made a fire, and rolled out our swags alongside the vehicles. This was all quite normal except that my travelling companion had settled down fifty yards away. He explained that he would be working on a bit and did not want to disturb me.

We had tea together, however, opening small tins and heating them as they were on the fire next to our billy, which was barely a third full of water from our valuable supply. It was a cold time of the year, and we stood by the fire talking over old times, old friends we had both known, and what became of them, until Bill, as he is known, although it has nothing to do with his initials [HA Johnson], decided to start work on the map. I gathered a good bundle of wood and put it by the fire ready to make a quick warm blaze in the morning when we would be very cold; then I lay down in my swag.

I woke during the night and was surprised to see the battery light still burning over at Bill's Rover, so I looked at my watch. It was half past two. It seemed like only a few minutes later that I vaguely heard a quiet voice saying it was getting late. I got up hurriedly, already dressed, and glanced at my watch by the light of the fire, which had obviously been blazing for some time. It was half past four! When I got to the fire, I was greeted with cheerful words of approval at my foresight in gathering the heap of wood. Bill said that he had come over to do that very thing when he had finished for the night, only to find it already there, and with that our day began on a pleasant note, as did every one throughout the entire expedition. I was curious about when he had finished working last night, and how much sleep he could possibly have fitted in between when I last saw him up and now.

Within twenty minutes we were on our way, with the headlights proving into the black bush and the cabin light showing me my vehicle compass readings. We had agreed that I should go in front as my vehicle was designed specially to take the main brunt of the battering and had as well the conveniently built-in compass. The other Rover had a canvas top and sides, which were more vulnerable to the persistent raking of the tree branches in the scrub.

We drove all the morning through many large patches of dense mulga, and as it would have been disheartening to constantly checked to see if the other vehicle was still coming. Once, after a particularly hard and difficult stretch of rough rocky washaways over dry creek beds lined with intensely heavy mulgas, I waited, but there was no sign of the other vehicle. After spending an hour checking my Rover for damage and anxiously peering back along the track, I began to wonder if it might not be quicker to walk back to see what had happened instead of driving. I wondered how Bill would be taking it after the few minutes' sleep he'd had in the past two days. Many a man would be near boiling point at having to travel through this country, and it is at such times that a man's true nature is revealed.

To my relief the sound of an engine came through the bush, punctuated at times by the noise of axework, and soon the Rover itself emerged from the wall of scrub. Any apprehension I had regarding the state of its driver disappeared immediately I saw the huge smile even before the vehicle had stopped, then heard the enthusiastic, louder than usual, happy observation, My word, we're getting along well now, aren't we? Bill had been chopping off every branch likely to harm his canopy and, as the same ones would be liable to damage those following as well, dragging dry mulga stumps and their roots out of the way. As a result, his vehicle still had its factory-new look.

We decided to check our latitude at midday with an observation to the sun, so Bill sent off a series of flashes to the party at the last point while I took the readings and finished the small calculation involved. He was rewarded by an answering flash, and after the compass bearings were taken and recorded ready for plotting that night and a predetermined signal sent, we hit the trail, as they say, the only difference being that here was really no trail to hit. We had seen another hill, on the western skyline, which was to be our next goal, and for convenience, although we were in radio communication with each other, we left a written message, indicating our latest intentions, on a stick in between the wheel tracks.

That night, having two flat tyres to mend after tea while the office work was going on fifty yards away, I thought that in this case I might be the one doing the disturbing. Before leaving the camp, I noticed Bill had dug a neat hole and buried our two tins, but at noon only my one tin had been buried. The thought that this was very neat and tidy, especially out in this country, put out of my mind temporarily the query about what had become of the other tin. This procedure was never overlooked throughout our trip, and it gave me a further insight into the natural thoroughness of this surveyor, which was not confined only to technical work, and it soon became a pleasure to observe and note the many things he did.

The next day we all decided to meet up for refuelling and compare our separate views on the going in general. No flashing signals had been needed for the last two points as they had both appeared on definite unmistakable hills, so that night we all camped together for the first time since setting out. We were astounded to learn that the supply vehicle had had seven flat tyres already; otherwise everything was going well and radio messages were transmitted to headquarters to that effect. We weren't to see much of each other at this meeting, for Bill and I were off as usual on a new bearing to a high sandhill that would have to serve as the next point.

At this stage we decided that a star latitude and longitude position would be of great help in the compilation of the map, so for once we stopped before it was quite dark in order to set up the instruments. I had mended my flat tyres at midday on this occasion and was lucky enough to see the afternoon out without another puncture, which left me free to concentrate on the stars. Later, with the observations done and the calculated position written on a piece of paper, I started out on the fifty-yard walk to the drafting office, taking care to leave my light on so that I could find my swag easily when I came back.

Bill seemed very glad to have my piece of paper with our position on it, and by the fire at tea time we had the usual discussion concerning the country and the survey. It was nearing midnight when we finished, so I hiked home again to my observatory and waiting swag where I lay down and was soon asleep.

The country was surprisingly free of the huge belts of heaped-up sand ridges that we had become used to on the previous leg of the project, and our journey was made over much more open spinifex that I had ever seen before. It was broken here and there by patches of thick mulga scrub, and as we passed through each one, Bill's little axe was often in action and I grew used to waiting at the far side for the never-failing smile and welcome comments about how well we were getting along. Bill had not had one flat tyre, and the canvas top was still unmarked which was a credit to the driver.

On another morning when we had again all met up as a party, I noticed that the supply vehicle and one of the Land Rovers had changed drivers. Apparently, the effect of the high centre of gravity - persistent rolling and pitching over the spinifex - had temporarily got the better of the original operator. We were told he had jumped clear, crouched down behind a clump of scrub so as not to look at the vehicle, and shouted the message into the air that he was not going to drive that thing another inch. It was understandable considering that in addition he had received over forty flat tyres. By the time they reached us his ill-humour had worn off and the drivers had decided to return to their respective vehicles.

Under one red rocky bluff we decided to use as a survey station we found some small caves, on the walls of which were aboriginal ochre finger painting, consisting of crude circles and zigzag lines, giving us definite proof that this region had once been inhabited. When we climbed the short distance to the summit further proof was to be found. A small rock hole, contained about a gallon of water from some recent shower; not unusual in itself, but the aperture of the hole had been stoppered against evaporation, and use by animals, with a well-fitting round boulder uncommon to the geological pattern at the top of the hill. This was certainly remote country, so remote in fact that it was in the Zone A taxation concession area, but nomad natives had known about it first. I was to be told over the radio transmitter long after our expedition was over that this particular hill was in future to bear my name - an honour indeed.

One night, as we stood at our campfire after we had again split into two sections, Bill made the announcement that he was going to be bed early. Every so often he felt that he just had to. He also said that we needn't leave in the morning as early as we had been doing and could really sleep in for a change. After this good news we talked about astronomy and I asked what became of the midday tin that was always missing from the hole. Bill showed me a box full of them, each carefully wiped clean with a rag, and explained that they would all be used for marking future survey stations as a guide to his follow-up parties. Made of rust-proof foil (aluminium), labelled in paint with the serial number of the point, and nailed to a tree alongside the wheeltracks, they shone in the sun, attracted attention, and served as a thoroughly effective and practical sign.

I would not have noticed Bill's meal that night, of baked beans and a dry biscuit, but for one thing: he'd had the same menu every night since we'd been at the mission, and kippersnacks from the foil container at every dinner camp. For a long while, Bill told me, he had solved and simplified his eating arrangements by setting out with a carton of each, and these together with powdered milk, dry biscuits, and a battery-operated razor made his bush life complete.

After helping each other to gather the little heap of wood for the morning it was quite late when we turned back our swags, and I fell asleep thinking that, despite the conditions, this was probably the most pleasant expedition I had ever made. We overslept until such a late hour in the morning that we had to use our headlights for a much shorter time than usual.

The next time the two parties met, much restocking and refuelling had to be done and the supply vehicle was almost completely unloaded. We could help them this time with our supply of patches, for they had run out, having ceased counting the total number of flat tyres after the fifty mark. I reflected that I had surely not been wrong about those bar tread tyres when I had seen them at the mission, but the vehicle itself was negotiating the rough going quite well and was still right there with us, which after all was the main thing.

Another astrofix that night checked our exact position, progress was plotted on the recce map fifty yards away, and we were ready to move off again in the early morning armed with a new bearing.

Several days alter we found ourselves on the banks of an enormous salt lake, so vast that it disappeared into an unbroken skyline. We knew that this lay to the north of our destination, so if we skirted the lake around its south-eastern shore, we must soon cut some defined station tracks that would lead back to the homestead. Our trip was quickly and successfully drawing to a close.

We all looked very dirty and disreputable, so we camped at daylight in order to find our clean shirts and rub a wet cloth over ourselves. This was using the water recklessly, as the most we could have expected throughout the previous weeks was a moist cloth. Since striking a station track, we had been able to drive well over five miles an hour, and in back-wheel drive only, so we felt in high spirits as we unrolled our swags.

A few miles farther, and the familiar sight of the flying doctor wireless aerials rising above the level of the mulga scrub gave us our first glimpse of civilization and an indication of the actual whereabouts of the [Carnegie] homestead. It was, as always in these circumstances, a relief after the weeks of bushbashing to be safely through to our destination and not broken down miserably somewhere, needing much wasted work of salvaging.

They already had word of our intended trip, as fresh supplies of fuel had been sent to their station by mail truck to wait for us. During the survey the supply truck must have had almost seventy flat tyres; the rest of us averaged about half a dozen or so each, with the exception of Bill, who thanks to his little axe made the whole trip without any…Central Australia had now been crossed from east to west for the first time by motor vehicle.

HA Johnson’s own 1958 photograph of his Landrover, personally captioned “100 miles west of Giles”.

Circa 1958 model Damlier-Benz Unimog. Georg Sander image

|